Deep Minimalism

Deep Minimalism is the topic of Geoff McDonald’s next book. It’s what you get when you apply the principles of Minimalism to all (or at least, more) areas of your life. The first slice of this topic is shaping as a standalone book, Minimal Work. In this podcast episode (#115 of the Ideas Architect Podcast), Geoff is interviewed by his good friend, Alan Silcock, author of Five Gifts Flourishing. This is the first time Geoff has been interviewed about Minimalism.

Resources

Resources

Download Podcast Episode

Download the Podcast Episode here

Transcript

Alan Silcock 00:09

We’re here to chat with Geoff McDonald, sometimes known because I’ve known him for so long as ‘Geoff the Juggler’. And there’s a story behind that. And Geoff, and I’ve been good friends for many, many years, ever since the ALSA, the Accelerated Learning Society of Australia, which, unfortunately, no longer exists. But when it did exist, many decades ago, it was sensational. And we’ve learned Geoff and me together through that organization, some really fundamental learnings around how we learn as humans, and that’s been of significant benefit, I know in my life as an author, and as someone who’s going to have their first book out next month, and then later in the year, my first novel, and certainly in Geoff’s life. He’s been a prolific writer throughout his life and a prolific ideas person throughout the time that I’ve known him and a delight to have a chat with him, which will be no different today. So Geoff, welcome.

Geoff McDonald 01:18

Thank you, Alan, it’s kind of a nice point to reflect on because back then I was studying architecture. And it kind of never made sense for me that I was going to this Accelerated Learning thing. I was coming up to Melbourne, and I was writing their newsletter and all of that sort of stuff. And it was kind of like, I was putting in all this time into Accelerated Learning, which had nothing to do with what I studied or what I thought. But it’s kind of when you stop and think and you make connections, and you view these things a bit more broadly, it’s like, well, I still see design or creativity is just a form of learning. It’s my way of exploring the world. And, and I think that’s where we’re bonded is that we both love learning and being curious about the world and ultimately creating stuff. So it’s kind of funny that we both finished up writing books.

Well, exactly. And in the title of my book that’s out and a couple of months, or a month or so is called ‘Five Gifts Flourishing’. And one of those gifts that I have, and I’m encouraging people to find their own gifts and have them flourish in their lives, is learning that sits in there as a call for me, and I know it’s a call for you.

Geoff McDonald 02:27

Well, it’s kind of a way of… I guess I get stuck with it. Because at one level, I go, how do you explain this? But I think sometimes it’s best to explain the opposite, that if I didn’t learn, I’d be repeating the same mistakes over and over.

Alan Silcock 02:43

Yeah, and you might even be lost.

Geoff McDonald 02:45

Yeah. And ultimately, I always wanted the business card that said, Geoff McDonald, Explorer.

Alan Silcock 02:53

Yeah, explorer.

Geoff McDonald 02:54

Explorer was kind of, Okay, I’m an explorer, I just want to explore the world. But I don’t necessarily want to, you know, I do want to travel around the world, but I don’t actually want to be going through deserts, maybe, but more than I want to explore ideas and what’s possible, and I think that’s the ultimate in creativity and learning.

Alan Silcock 03:09

Yeah, and from the time that I’ve known you, certainly are an explorer and willing to engage in areas that maybe not that many people are. And I guess that’s, that’s certainly what we’re here to talk about, which is your latest, I know that you’ve written a number of books, and the last of those that was published was ‘Done: How to finish your projects when traditional ways don’t work‘, and they’re snappy little books and really helpful books. And today, we’re here to talk about one that is currently underway and will hit the streets in the future. And that is,

Geoff McDonald 03:50

The working title at the moment is ‘Deep Minimalism’. I guess this is probably a similar question for you. It’s like, what are you going to write about? And this one kind of came around… Someone just said something to me, really, you know, just part of a normal conversation that was like, well, you’re living a minimal life anyway. Why don’t you write about that? And I had already written notes about what I was doing and how I’d been doing it. And I just, I’ve been looking for different stuff. And in the finish, I just said, okay, that’s the one I’m actually been living it, I might as well tell people some of the things I’m doing. Yeah. And when you look at the minimalism conversation, it’s nearly always about having less stuff. Yeah, no, that’s the one people and I realized, well, actually, there’s more to it than that, because I think it’s actually a philosophy rather than just a set of action.

Alan Silcock 04:42

How does that differ from a set of actions, compared to a philosophy or movement, if you like?

Geoff McDonald 04:48

I think philosophy is a deeper piece. So you would, it’s a bit like, I might have a value, I might value something, therefore, I act in a particular way. Yeah. My simple definition of philosophy is that it’s a way of seeing the world’. And so if you see the world in a particular way, and in this case, if I see the world as fundamentally, ‘less is more’.

But there’s also another piece, I think the fundamental piece, if you look at it, psychologically, is that we get our happiness internally. There’s no happiness out in the world. Yeah. And that is simply a way to explain. I don’t need more stuff, because that’s actually not going to make me happier, I might want more stuff, and I might still buy stuff, but I don’t actually have to crave it anymore. And after I got rid of all my stuff, when I started moving house, a few years ago, it just became really obvious I’d always lived almost a student lifestyle, anywhere where I’ve never had lots of money. I’ve always lived pretty leanly. I’ve never really craved a lot of things. So it was kind of second nature to me to operate in that way.

Then I started house sitting for a while. And it’s kind of like, well, that’s minimal living. Yeah, you know, I had friends asking ‘how was homeless Geoff going?’ because technically, I was homeless, because I didn’t actually have a fixed address, which is kind of the definition of homelessness. And when you start to then apply it and go, Okay, well, how would this look around my diet? Or how would look this in the mindfulness space, or there’s a great book by Cal Newport called ‘Digital Minimalism’. So how do I do digital, but in a minimal way? And it’s kind of becomes this whole way of looking at life and not just about the stuff, I have to own or all the things I have in my house. And that’s kind of what I mean, by philosophy. It’s this way of operating in the world or even seeing the world rather than just a discrete set of actions.

Alan Silcock 06:43

So it seems to me that and I because I’ve got three young men who are in their early 20s to 30s, these days, and all three of them at some stage, refer to what you’re talking about and guide their lives around what you’re talking about. One of them, Callum, for instance, travelling around the planet for over a year out of a minimalist approach, in terms of living in terms of moving. He left London recently to get back to Australia. And I’ve noticed and forming how they’re going to be living next. Currently. Yeah. Is it something that is specific to that generation, to sort of generation Xers and beyond? Or is it something that, you know, that resonates with a broader group of people?

Geoff McDonald 07:47

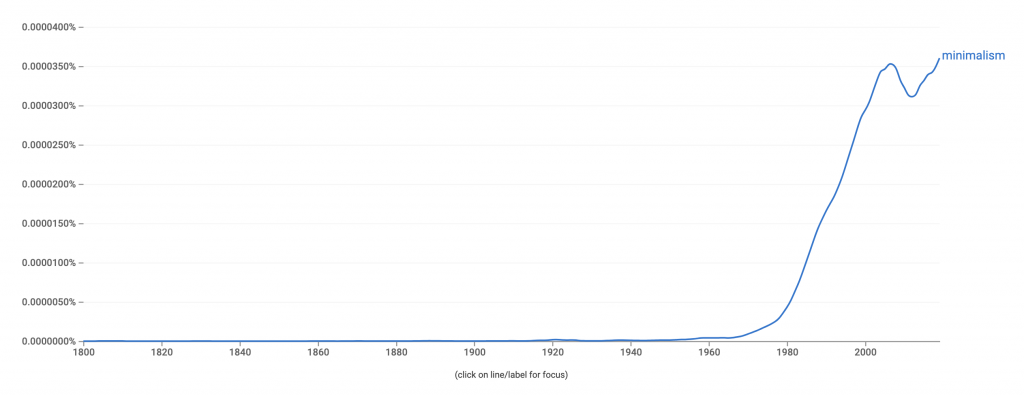

Yeah, it’s a really good question. Because what I’ve been trying to find out is where it all starts. Yeah. And there’s a type of Google search, it’s called, you can type minimalism, and Google can tell you where it’s been searched. But there’s also another one where Google’s got Google Books [Google Ngrams]. And it can actually tell you that word usage over time. Yep. And the word minimalism almost has no use usage up until the 1960s. Then it kind of spikes to about 2000. Yeah, then dips, then it comes back up in the last five years. So there’s certainly something about it being contemporary, generational, all the rest of it. If I was to put a big picture view on it, there’s probably two things I’d say. So the first one is the Industrial Revolution comes along, we get all these machines, all of a sudden, we can pump out almost anything. And this explodes after the Second World War, where we’re buying fridges and cars and washing machines. And all this stuff is now cheap. People could buy houses. And we kind of get to the point where we can have more, more, more, more and more. Add some credit in there. And people, particularly in the Western world have got, let’s say it this way: they’ve got lots of stuff.

Alan Silcock 09:03

Oh, so much stuff. They need to put them in storage units out of their property.

Geoff McDonald 09:08

Yeah, you got to know you’ve got a problem when you go too much stuff in your house. But if the other side of that point is if you look at the origin of it, and partly because I’m an architect, I looked at it as an aesthetic that came out of the modern movement in the 1920s, particularly in Europe. And they were starting to fight the Industrial Revolution piece, because they were talking about machines, building buildings, as distinct from handmade buildings, which had decoration, all the rest of it. So they were talking about it from an aesthetic point of view that less and that’s where ‘less is more’ kind of got phrased.

But I think there’s actually an earlier point than that, and the Japanese would never call it this. But if you go back to Zen Buddhism, and everything around the samurai actually was about living a minimal and perhaps a simple life, not a minimal life. They might have said a simple life. Yeah. But they kept it. The samurai is a good example because they basically, were highly tuned into whatever they were doing at that time. So if I’m eating I eat. It’s the whole mindfulness approach, which comes out of Zen and Buddhism. And that’s probably as close as you can get to what minimalism actually comes from, even though the Japanese would never call it that.

So I think there’s a simplicity of life and a philosophy of simplicity from way back then. And you could probably draw a fairly comfortable line and say, in the last few years, meditation, mindfulness, and those notions of simplicity, have come back. And I think that’s almost a complete reaction to everything has just got so friggin complex and chaotic. And what’s important. Certainly, the pandemics brought that home for people as well, to come back to what’s important here.

Alan Silcock 10:58

So can simplicity generate satisfaction?

Geoff McDonald 11:05

Yeah, I think it can. I think I hinted at that before, or when we were talking earlier about, where does our happiness come from? Yeah. And there are some interesting studies on consumer behaviour. So people think, Oh, yeah, I’d love to have that shirt or that new computer or whatever. And it will make me happy. That’s kind of a presumption, but it’s actually a marketing position. They’ve actually told us to buy this car, buy this computer because it will make us happy. What psychology shows is that the point where you’re most happy about any of your purchases, is in the instant, before you hand over your money.

Alan Silcock 11:42

Yes, that’s right.

Geoff McDonald 11:42

Before you hand over the money. Before you actually buy it. And that what I saying is, if you really want to be happy, grab the thing off the shelf, walk up to the counter and say, I’ll have this please and just before you hand over your card walk away.

Alan Silcock 11:56

That’s right, isn’t it? Because I’ve also been studying significantly in the area of mindfulness and a number of studies which lead to say that, you know if you do get that car that you want, and you’ve always wanted, or as desired. Yes, that point that you talk to strikes as the most significant point. But then even if you do buy it, it’s only a matter of a couple of weeks down the track that you’re not as happy is worth. Yes. Yeah. And attracted to that, just like it’s a minimal amount of time, that you’re still deriving pleasure from this thing that you bought two weeks ago.

Geoff McDonald 12:30

Yeah, there’s a great TED video [The Surprising Science of Happiness]. I can’t remember the guy’s first name, but it’s Professor Gilbert from one of the US universities. And he tracked people who had won lotteries. Yeah. And yeah, that researcher, and he also tracks people who’d become extremely unwell or become a paraplegic or something like that. And basically, there was something like after about three months, their levels of happiness had returned to what it was before prior to winning the lottery. So I think the view that we can be happy by external things is actually true, but it’s short-lived,

Alan Silcock 13:07

It’s short-term.

Geoff McDonald 13:08

And there’s a much deeper resonance, happiness, satisfaction level generated from within ourselves. And that’s kind of what I think the point is that the Japanese or the Buddhist would say that the world and my room, is actually a reflection of what’s in my mind, or my heart. And when you take it from that perspective, you can see that if I get myself in a good space, then everything else will just take care of itself. And we’ve been told a bit of a lie around happiness, that you actually have to have all these things before you can be happy. Yeah. Whereas what the truth is, you can actually be happy now. And the beautiful part is if you’re happy now you’re more likely to work harder and be successful. So you can actually have it but you’ve got it around the other way.

Alan Silcock 13:55

And achieve and have that level of satisfaction throughout your life.

Geoff McDonald 13:58

Yeah. And mindfulness is a really good example of minimalism. You know, do you have the monkey mind or the chatter in your head? Yeah, versus if I can just become at peace with myself. I’m not going to want and crave ice cream, or the new car or whatever.

Alan Silcock 14:16

Today, as part of my discipline, which I talked about in ‘Five Gifts Flourishing‘. Every morning, I go for a walk. And every morning I ask myself three questions influenced by Buddhists. And the first question is, what am I grateful for? And this morning, I noticed as I asked myself that question, what am I grateful for? I didn’t have the answer until I took a breath. So I’m grateful to have this fresh, beautiful lively air in my lungs, every day. I’m in the city, and I’m still going into the park and I can breathe this beautiful air. I’m grateful for that. And there are other things that come up.

Just doing that on a daily basis for me, and also looking at kind of the opposite of that, which is, you know, what are the facts? What is the impermanence that I face every day? It delivers me a great way to focus one day. And I do agree with you, Geoff, that simplicity in just doing that, like, there’s no there’s nothing complex about it. I’m not out on a million-dollar bike, driving in the hills in a million-dollar car. I’m just walking in a 20 buck pair of runners, you know, a shirt I’ve had for about 40 years. You know, people avoiding me obviously. And yet, it’s such a simple, delightful thing to do. And I always stand beside the fountain in Victoria Gardens, which is a delightful fountain, and do a bit of Qi Gong that I learned when we studied the ontological equation some years ago. And it’s delightful. It’s such a great way to start the day.

Geoff McDonald 16:13

That’s a beautiful example. It costs you nothing. You can do that whenever you want. And it takes minutes.

Alan Silcock 16:20

As long as I can walk, I can do that.

Geoff McDonald 16:22

But it’s also easy to dismiss that as some sort of trick shot. Yeah, as distinct from this is actually quite profound if I’m willing to stop and consider that, compared to a lot of the other things, I decided about life. I need that, I want that, I must have that. Or if something goes wrong, and we, make a mess of ourselves as well. There is something that’s easily missed here.

Alan Silcock 16:51

Yeah. And, you know, unfortunately, you know, my other research into mindfulness, and in the Buddhist psychology side, is that there’s a McDonald’s mindfulness starting to appear. Where, you know, people are starting to charged people a lot of money, for instance, to find out what satisfaction is within? Well, yeah, as the story I’ve just told you, doesn’t cost you anything really. You shouldn’t have to. And that’s a simple thing in itself. What if you could just do it for yourself, you know, you don’t have to pay a guru 1000s of dollars to take you through in programs, you know. Yeah.

Geoff McDonald 17:40

Well, there’s always a McDonald’s point of view, from an aesthetic point of view that you can buy simple furniture. But you kind of can live it as a stylistic thing rather than as a genuine thing. And the other one is, you can have lots of stuff that you can hide in cupboards. So you walk into the room, and it all looks nice and simple and clean. But the reality is, you’ve got a whole bunch of clutter somewhere.

Alan Silcock 18:04

Yeah, well, that’s the case with the artwork. You can have heaps of pictures up on the wall. What’s the point in having them in secondary storage?

Geoff McDonald 18:13

Yeah. There’s also a flip side to this, though. So when I’ve spoken to my mom about this, it’s like, well, the house looks so bare. Yeah. And it’s kind of like, Well, yeah, that’s the whole point. But, it’s kind of this expectation about or this standard, or this, it should be a particular way. And the big challenge at the moment, you’re writing about minimal work. And the idea is, well, if you could actually get all your work done in four hours instead of eight. Most people go ‘Hey, fantastic. I love that.’ But then there’s almost like this. ‘Oh, hang on’. There’s this pregnant pause. And I remember when Tim Ferriss wrote his book, ‘The Four Hour Workweek’. So he was talking about four hours across a whole week, not just a day. And he said the biggest thing that stopped people was not actually having a four-hour workweek. But what the hell am I gonna do with the rest of my life? And this is kind of the other side of this equation that we could have a whole bunch of other things happen. But there are always consequences. Because if you only had to work four hours a day, what the hell are you going to do with the rest of your day? Or if I didn’t have something on the wall? What am I going to put there? Or if I didn’t have my monkey mind? It’d be quiet, wouldn’t it?

Alan Silcock 19:26

I gotta fill it. Yeah.

Geoff McDonald 19:28

But that’s also the craving around the happiness and the willing to be at peace or willing to be with yourself or willing to be with your thoughts, that it does force you to a deeper level of engagement with yourself, and probably with other people. Because ideally, you’re not going to take the cheap way out and just, ‘Well, I’m feeling crap today, let’s go buy a new TV.’ And that might be helpful or it might not be a very good strategy at all. Whereas if you could actually sit down – this is classic around food.

Alan Silcock 20:00

Yeah, that’s interesting.

Geoff McDonald 20:01

A lot of our food is emotional eating because we have a sensation in our stomach, and we go, ‘Oh my god, I must be hungry. I should eat ice cream.’ And I love my ice cream. But from doing fasting, I’ve been told that the key to your hunger is not in your stomach. And it’s not a feeling there. It’s actually a taste on your lips. Yeah. So if you want to go, I’m going to manage my food and be minimal around what food I eat. Then there are certain ways around it rather than again, bouncing out of some emotional, reactive space into buying something, eating something, and so forth. Yeah.

Alan Silcock 20:39

So is there no room for indulgence?

Geoff McDonald 20:42

No, not at all. I think we talked about this before about having a beer that, you know, we’re here to enjoy ourselves as well. But the point is, by all means, have a beer. Just know that beer is not the secret to happiness. But it might be fantastic right now because it’s bloody hot and the cold beer is beautiful. So it’s kind of where are you going consistently for your joy? And, by all means, have a beer, by all means, go and yell at the referee at the football. But just don’t try to make that your go-to position. That’s probably what I’d say.

Alan Silcock 21:18

Yeah. Okay. What’s the MLP? The Mindful Life Program – That’s stimulus-driven happiness? Yes. As a distinction from genuine happiness. No, sorry, let me rephrase that. Stimulus driven pleasure as a distinction from genuine happiness. Yeah, so there is room for stimulus-driven pleasure.

Geoff McDonald 21:44

Absolutely, otherwise, you’d be a monk sitting down meditating for the rest of your life. You’d be very happy, but you wouldn’t really go a great life.

Alan Silcock 21:52

Yeah. You wouldn’t have that those pleasures in your life? Which do contribute to our happiness in some way, too. Absolutely. So what about so you’ve talked about food. Can you tell me more about the work side in terms of minimalists? Like maybe even bring it into an organizational setting? How can you have a minimalist organization?

Geoff McDonald 22:20

Well, I look at it from the basic principles. So you’re trying to do more with less. So it’s very much what all of our productivity stuff is talking about: how do you get more done with less effort or less time or less attention? So the same would apply. So one example would be… There’s some interesting research around work where, basically, so we’ve got the problem in a lot of organizations around mental health challenges. More people seem to be running into problems around that. So what’s causing that? And there’s probably a number of things.

One of the things that I’ve kind of picked up on is that there’s research out there that says, We’re probably our brain works from a high-performance level for about four hours a day on task focussed work. After that, you’re probably either dropping your performance or depleting your wellbeing at some level. Yeah, in the sense that the extreme example would be, I can’t do 12 hours a day on a computer all day, because eventually, I’m going to be a wreck. So that kind of says, if we use that as a benchmark, rather than a limit, we can go ‘Okay, what sort of work could I do during the day? And what type of work do I have to do?’

So you might go, if we’re going to use Cal Newport’s idea around doing Deep Work, which is strategic work, thinking work, study type work, to come up with new innovations, or even just think about our way forward, or planning or write books, whatever it might be, then you might limit yourself there to four hours of work a day.

This is consistent with some historical figures that have been writers and researchers and the rest of it. A lot of them did not write for 12 hours a day. They wrote in small chunks, and then took breaks. And that actually fits in with brain research. Our brains this, what they’re coming up with, there’s two types or two parts to our brain. There are a few different models here. But one of them’s the Uptime brain, which is task-focused. Yeah. The other one is the Downtime brain, which is kind of connect the dots brain. So when you’ve been in the shower, and you’ve come up with the idea, that’s because you’ve switched out of the task focus, and you’ve gone into this Downtime brain. The brain is going that fits for that. And that fits that. And ideally, we should be cycling in and out of that.

Alan Silcock 24:17

Yeah, that that makes a lot of sense. And I’m just thinking the way I do my own life is like that. I’ll do task-focused stuff for a few hours at a time. And then I need to do something else to stimulate. So it’s either having a conversation or it’s walking or it’s, it’s something or it’s reading or it’s something else that allows by two hemispheres to connect.

Geoff McDonald 25:02

Perfect. One of the things I’ve started to tease out is this idea of a Three-Phase Day. So the three phases are one would be task-focused work. Yeah. One is the downtime work. And one is some sort of rest and recovery. Yeah. And the downtime piece might be the socialization. The classic way, you can apply that if you’re a solo entrepreneur, let’s say you’re a coach or something like that, where you might do your study planning strategic stuff, or your computer works for a couple of hours each day, then you might talk with your clients for a couple of hours a day, then you might have to time off to go for a walk, ride your bike, exercise, or just hang out with friends. And you’re actually cycling in and out of that rather than doing long sessions in each of those phases.

Alan Silcock 25:51

So I think that’s what I do naturally.

Geoff McDonald 25:54

I think that’s the interesting point.

Alan Silcock 25:56

That is, yeah, for me, it’s evolved. But it works for me. Well, it actually is a certain time of the day. Like, once I’ve done by, as I explained before, early morning reflection, and my mindfulness stuff, I’m set to do other stuff, I can dive into it, I chunk it in and get it done, you know, and I’ll get to the end of that, and I’ll need to do something more creative.

Geoff McDonald 26:24

Absolutely. So one of the concepts I’ve been sharing with people that seems to resonate is the idea of ‘Work like a human’. So if you think of where our work comes from, it actually comes from the Industrial Revolution, someone standing next to a machine for 12 to 16 hours a day going clunk, clunk, clunk, clunk. Yeah. But humans are not like that. We need breaks, we need socialization, we have good days and bad days, we need some variation. And there is some more of a natural flow or rhythm about how we could be working rather than expecting to be consistent all the time. The other piece that’s on this is we need to know that social media is not a break for the brain. If you think about it technically, the brain just goes I’m sitting at my computer tapping on things still, it doesn’t know whether you’re having fun on social media or whether you’re chatting to your boss or writing a report. So we’ve got to look at the things that actually are our recovery, and have them as distinct recovery.

Alan Silcock 27:27

I totally agree with that. No, just read another piece on that. Yeah, it’s it feeds the monkey mind. Alan B. Wallace has some nice pieces on YouTube TED Talks, where he passionately talks about, you know, how if we entertain the monkey mind it’ll just take over. We’re really not doing anything to help ourselves escape at all. Quite the opposite, we’re imprisoning ourselves by embracing social media, not the opposite.

Geoff McDonald 28:05

Yeah. And even down to socialization is very important. So some people are showing up at work and being lonely. That’s a problem at one end of the scale. The other is people not spending time alone. Yeah. And, you know, being surrounded by or having their phone constantly chatter to them is not switch-off time. Now, that’s being on alert all the time. That’s building distraction. It’s building the habit of distraction because fundamentally, this is about habit.

Alan Silcock 28:31

Yes. You know, well, it is a bad habit. And I don’t know if you saw the documentary on social media recently, where they had, I can’t remember what it’s called, but it was it had it featured some of the leaders, the guys who invented things the ‘like’ on Facebook, and you know, the architect, and you’ve probably seen it, and to a man the dozen of them that were on that show said they would never have their kids engage or very little engagement in social media.

Geoff McDonald 29:04

Yeah. Well, there’s no accident that Facebook has the nickname ‘crack book’ because it’s like crack because it’s been designed to grab your attention and keep it there for as long as possible. So these are organizations that are basically buying your attention because they want to sell you stuff or expose you to ads. I have nothing wrong with that. But you need to know what you’re buying into when you sign up.

Alan Silcock 29:26

Exactly. And, you know, you need to have strategies around your exposure to stuff like that. Yeah. That are as you have suggested helping you to gain a balanced workday. That makes sense. Otherwise, you know, it’s gonna be stimulus-response like that little buzzer. Does that mean we get our beer now, Geoff?

Geoff McDonald 29:56

It’s Pavlov’s dog. The buzzer goes off. Or it’s beer time. Great.

Alan Silcock 30:00

I’m really fascinated by all that stuff at the moment because I just see so many people caught in the same way as you know, the hook to gambling online and in pubs and clubs and stuff. And it’s insidious.

Geoff McDonald 30:14

Well, no accident, they have poker machines and the casino environment are designed in the same way that Facebook was. They’re designed to shut out the external calls to go home. And it’s designed to keep you playing for longer. You just need to know that that’s what’s going on, then you can choose around it.

Alan Silcock 30:31

That’s right. So if that’s the downside, what’s the upside if we turn away from that, or you know, or experienced that judiciously? What’s the upside to being more minimalist in our approach?

Geoff McDonald 30:44

I think for the person there’s a calmness, a peacefulness and a more meaningful life because it’s kind of like if I’m putting it this way, if I’m only going to spend four hours of work a day, I’m going to have to be pretty clever about what I choose to focus on. Yeah. And probably by implication, that means that’s not important. That’s not important. That’s not important. And all of a sudden, I’m much freer. I’m not trying to get as much done. So there’s a personal value around calmness, happiness, meaningfulness.

The spin-off on this is though if you actually read the habits books. Professor BJ Fogg is the world expert on habits. And if you read a book on habits, it almost nearly always comes back to his research, even if he’s not quoted. One of the things one of the Maxim’s he’s got in his book called ‘Tiny Habits‘, is that people best change when they feel good about themselves. And if you think about that, it’s kind of commonsensical. It makes just obvious sense, of course.

So what he’s saying is, if we actually want to change anything about ourselves, we first got to feel good. So if we can actually put ourselves in a place where we’re happier about stuff, yeah, we don’t actually have to rely on the external fixes to make us happier.

And the same applies to climate change. So this might be stretching a bow, but this is kind of the connection, I see that on a good day, I can quite clearly go, ‘Hey, we need to do something about the climate’. But when I’m stressed and anxious, and my bandwidth has shut down, and I’ve got to get that report out, yeah. I don’t care about climate change.

And I think that’s the thing if we can start to see that these external panaceas, these external pills, and even the external vaccines we’re trying to take to solve basic, human immune system problems, do work. But we don’t want to rely on them. Yeah, that if you change at that level, then the potential to relate to problems like climate change shift too. And I’m not saying it’s the instant fix. Yeah, it’s an orientation that has our start to say, ‘Hey, this is something important here. We should probably address this.’

Alan Silcock 32:58

Yeah, I do understand that. From like to just think we go on holidays, right? Yeah, you spend the first week not really been detoxing. And they get to the end, and you’re heading home. And that’s the time when you think I’m gonna do this, I’m gonna do that go into that and you get to the office the next day, it all disappears, right. But of course, the opposite of that is, you know, being in that place where you can make change happen is the place where you just had a disaster in your life. Yes. And you have to make change happen. So at both points, I think change is possible. Sometimes, unfortunately, I’ve found as a change agent over 30 years, that disaster has to happen in someone’s life in order to turn them enough to say ‘shit, I’m going to do something differently.’

Geoff McDonald 33:46

Well, I think it’s a beautiful way of describing the pandemic and the lockdowns, people, including yourself have been through. If we’re ever going to get a forced reset, that’s got to be pretty close to it. We’re not going to get a better wake up call. And then and partly what prompted me to start writing about this was that I could hear people wanting to make change happen. And they may not have known the direction but they kind of going ‘Okay, that last bit I was living, that’s not quite how I want to keep going forward.’ So there is a moment of change here that I think on the planet, as a scale is available as well,

Alan Silcock 34:21

Perfect timing. So when will we be able to see another book from Geoff McDonald on this topic?

Geoff McDonald 34:30

I’m aiming by the middle of the year, so mid-2021. At the moment, I’m just picking off Minimal Work. And I’ve got a four-week program running around that. And what’s emerging is that’s a big enough topic that might even be a separate book. At the very least, I’ve got an E-book coming out this week that summarizes my seven principles. And I might even turn that into a book in the next month and just make it a shorter one.

Alan Silcock 34:54

How can I get hold of that in the meantime?

Geoff McDonald 34:56

The usual place Geoff McDonald dot com is my website. Pretty much once they go over there they can find me and see all the stuff that’s on there.

Alan Silcock 35:04

Go and purchase it, folks. It’s good stuff. So it’s pleasure Geoff chatting with you again. And I thoroughly enjoy these moments as I do our friendship over many years and know that it will continue in a minimalist way.

Geoff McDonald 35:20

In a minimal way. Minimal friends, that’s another story. Thank you, Alan.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS